Ironstone Quarrying around Hough on the Hill

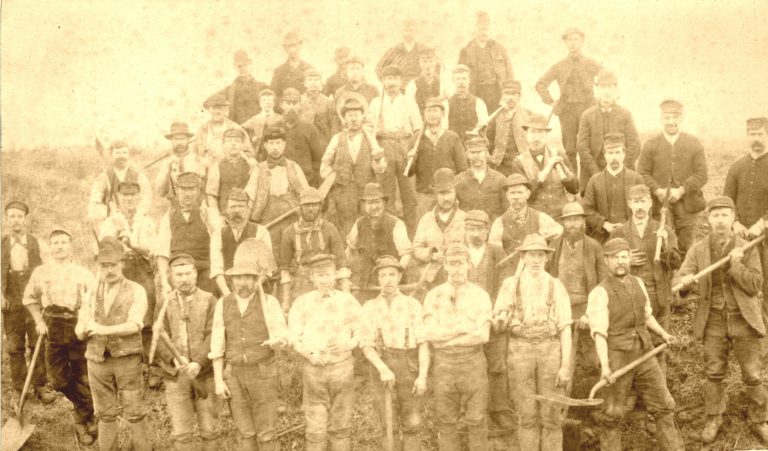

Large parts of the local area were quarried for ironstone in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of the men from Hough and Gelston were employed as ironstone ‘miners’.

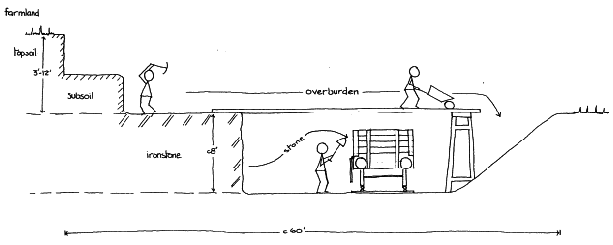

The crops of red marlstone containing 20-30% iron ore were typically shallow and the topsoil and subsoil were replaced once the ore was removed, so the excavated areas are now only noticeable at the edges.

Local Quarries

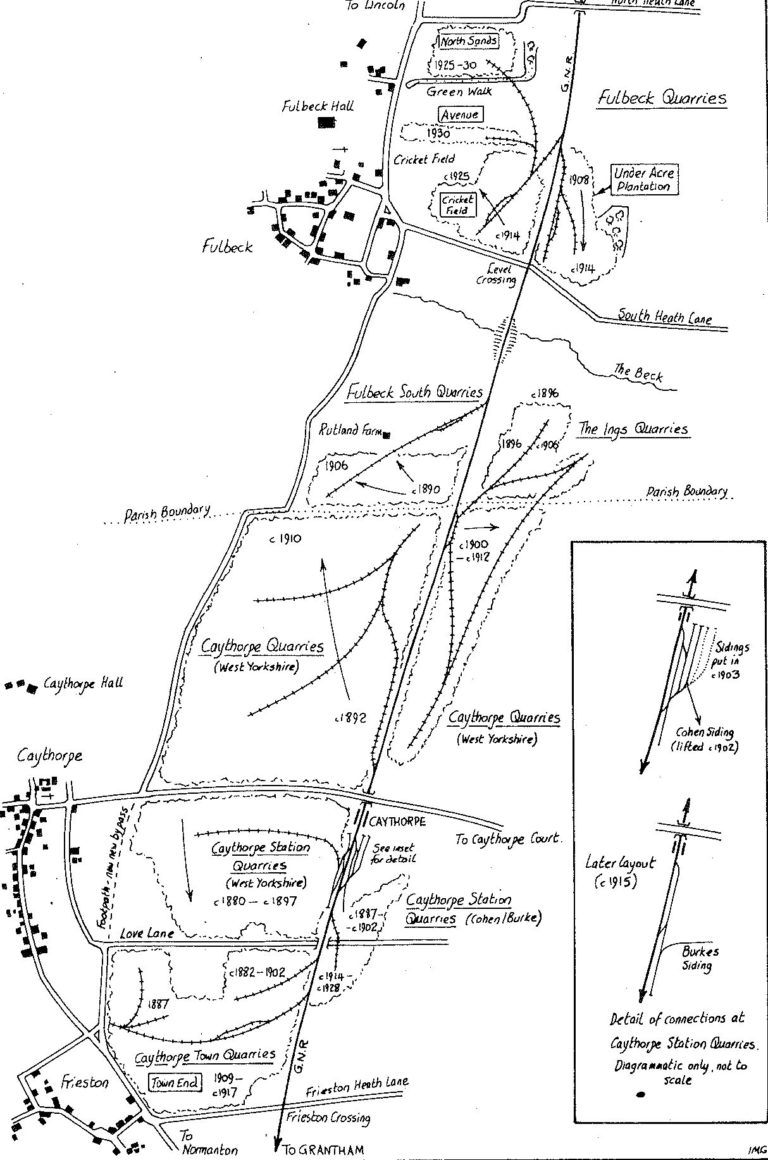

There were quarries all along the Lincoln Edge, from Harmston down to Honington. The first in the Caythorpe/Hough area were opened in the 1870s on land owned by George_Hussey_Packe of Caythorpe Hall. Packe was the chairman of the Great Northern Railway (GNR) which had opened the branch line from Honington to Lincoln in 1867 (closed in 1964). The railway was vital for taking the heavy stone to the iron smelting works. Railway sidings were run from the Lincoln line all the way to the quarry faces.

In 1873 the Grantham Journal reported that there was a large quantity of ironstone in Lincolnshire.

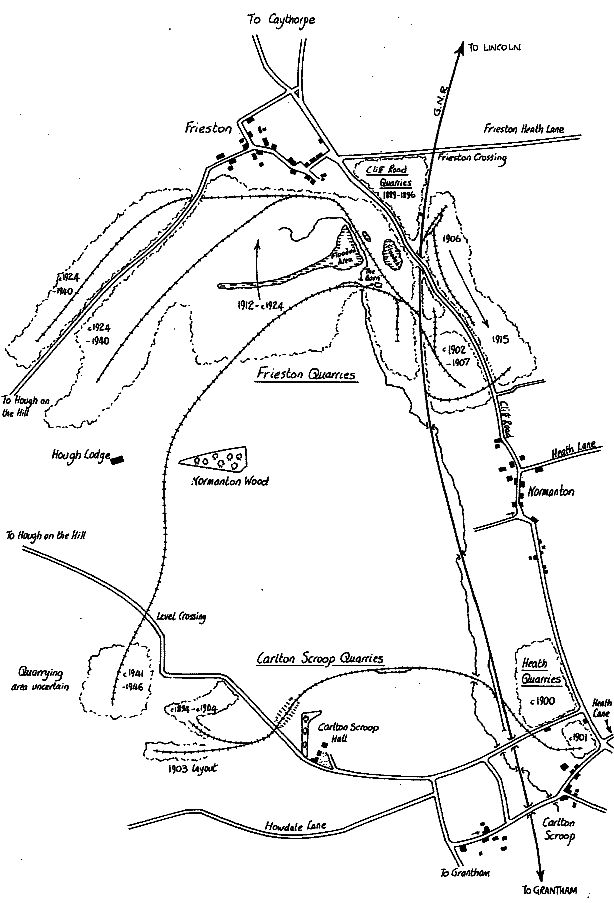

Walter Burke then opened quarries to just south of Frieston, initially close to the GNR line but then extending westwards, almost to Hough on the Hill on both sides of the Hough-Frieston road. The workings to the north of the road were reached by passing under a bridge (which is still there). Whilst most quarries used GNR locomotives to move wagons around, Burkes operated their own locomotive ‘Munition’ bought new in 1918 (and a 2nd loco 1924-32).

In 1936 Burke’s introduced mechanical excavators, though perhaps not on the scale of the machine shown in this 1943 film extract from a North Lincolnshire ironstone quarry.

By the time the Frieston/Hough quarries were exhausted in 1946, up to 160 acres may have been quarried.

Carlton Scroop Quarry

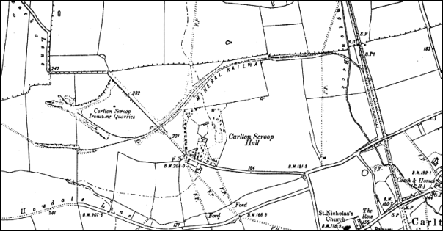

In 1892 a quarry was opened near the railway in Carlton Scroop. Three years later another quarry was opened by Attenborough and Timms to the west of Carlton Scroop Hall. A railway siding ran to the north of the Hall, with a stiff climb up to the hill, crossing the Hough-Carlton Scroop road by a level crossing.

In July 1903, following the death of Richard Attenborough, the lease was taken over by the West Yorkshire Iron & Coal Company (who operated the Caythorpe quarries) but following a brief period of increased production, the field was closed in 1904.

The quarry reopened by Burke’s in 1940 because of the wartime demand for local iron ore. A siding was laid across the fields from the Frieston quarry. The Carlton Scroop field was also closed in 1946.

See also Honington and Barkston Quarry.

Methods of Working

Up to the 1930s, all work was done manually, using picks, shovels and barrows.

The main area of activity was at the exposed stone face, about eight feet high. Here, the stone was dug out with picks and loaded directly into railway wagons, a siding running parallel to the working. Explosives were used to open up the seam. Arthur Nicholson of Hough on the Hill was only about 19 when a charge went off prematurely and blinded him. ‘Blind Arthur’ returned to Hough where he earned a living by making baskets in a shed behind his cottage at Crow Park (Wildnerness Cottages).

In Dec 1916 there was a collection (by Arthur Cooling) in the Caythorpe and Hough Ironstone mines on behalf of C Nicholson, a miner who had been unable to work for 2 years due to illness. This may well have been Arthur’s father Charles. £7 was raised.

In Nov 1910 George Marston (who lived in Gelston) was working at the Normanton quarries when a large stone hit him on the head. Blasting was in progress and owing to the thick mist he didn’t see it coming and was seriously hurt. Dr Baines was summoned to the scene and ordered him to Grantham Hospital for an operation.

Ahead of the stone face the 3-12ft of overburden (topsoil and subsoil) was stripped to expose the stone. The subsoil was moved to the lower ground behind the face, with the topsoil being spread over it.

Where the necessary clearance height over the railway siding could be gained, soil and subsoil were barrowed along a walkway supported from the lower end on trestles. Behind the working area the soil would be tipped from the end of the walkway, from where it would be re-spread. The walkway was a narrow plank and great dexterity was needed to balance along it. All the workers were paid on piecework rates, so much per cubic foot, so men would travel along as fast as they could. Boys from Hough used the planks as a playground.

But it was dangerous place to play or to work. In August 1897 Thomas Jackson was wheeling a barrow along a plank when the barrow fell off, taking him with it. Nobody seems to have thought to apply a splint before sending him in a cart on a painful 8-9 mile journey to Grantham Hospital.

Loading stone into wagons must have been hard physical work. Only the top of the face could have been thrown down into wagons; as it got lower, stone had to be thrown up. As the working face moved forward, the railway siding was moved to keep pace with it. When this was needed the workforce would stop production to push the track sideways.

The length of the working face varied according to the area under lease. Because of the need to slew the track, however, it had a linear formation. Only about 5% of a leased area was taken up by the quarry at any one time. Quarrying was therefore lucrative for a landowner who could carry on farming and get royalties on the ironstone removed. This type of quarrying meant that the area was not suitable for landfill, unlike later quarrying undertaken by mechanical excavation.

The loaded wagons were gathered in the various sidings and then sorted into trains at Caythorpe station, prior to despatch to the ironworks. The GNR wagons normally carried 8.6 tons of stone.

The quarries seemed to have opened at the about same time as the 1870s slump in agriculture. In 1905 the Grantham Journal reported that ironstone men were always better paid than agricultural labourers. An ironstone labourer working 4-6 days a week could earn more than 17/ whereas an agricultural worker might only earn 10-12/ some weeks. However, it could be dangerous work, for example:

In Oct 1886 Frederick Marston of Carlton Scroop (son of James Marston of Normanton) was on a truck at Caythorpe ironstone works when he slipped. To save from falling on his head he jumped and fractured his ankle. He was taken home in a trap and a telegram was sent to Mr Mason (bonesetter) of Grantham.

In Jan 1891 William Southwood from Gelston (aged about 18) was working at Caythorpe quarries when his left leg was badly shattered through a large piece of ironstone falling on it. On arrival at Grantham Hospital it was found necessary to amputate.

Sources:

The Lincoln to Grantham Line via Honington (Stewart E. Squires)

The Ironstone Quarries of the Midlands History Operation and Railways (E Tonks)

Grantham Journal

Hough on the Hill History Society

Me and the Parish of Hough on the Hill (John Keeble)